A carbide blank is a product that has already gone through the complete metallurgical sintering process and achieved the essential physical properties of cemented carbide , but has not yet been ground to its final geometry or coated. These blanks are the foundation of all tungsten carbide products you see on the market.

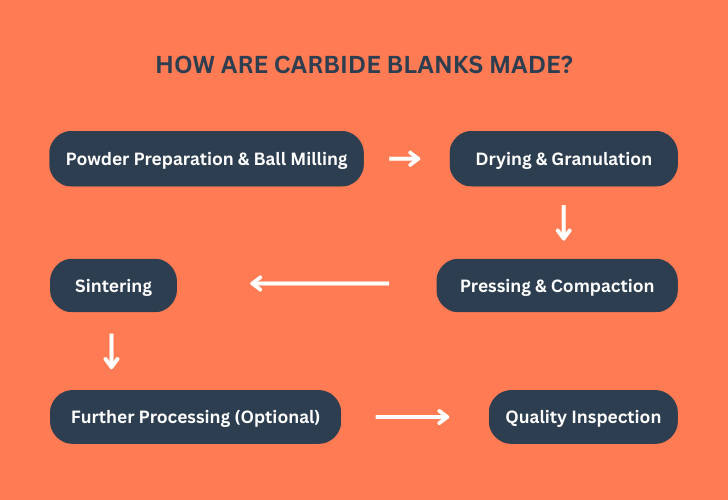

So, how are tungsten carbide blanks made? Today, we are going to walk through the manufacturing process step by step. When you know what happens before grinding and coating, it becomes much easier to compare different carbide blanks manufacturers and identify reliable suppliers for your specific applications.

Step 1: Powder Preparation & Ball Milling

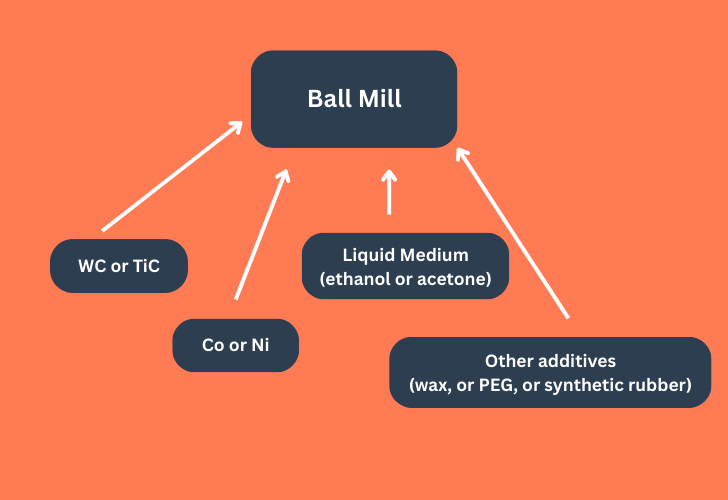

First, the raw material powders are weighed and blended according to a specific formulation. These powders mainly include carbides such as tungsten carbide (WC) and titanium carbide (TiC), along with binder powders like cobalt (Co) or nickel (Ni).

A ball mill is then employed to mix and mill these powders. Besides, a liquid medium, typically ethanol or acetone, is also required in the ball milling process. It plays several important roles during milling. First, it helps prevent oxidation by limiting the powder's contact with air. Oxidation at this stage would directly affect the final performance of cemented carbide blanks. Second, the liquid absorbs heat generated during ball milling and provides lubrication, which prevents excessive temperature rise and powder sticking to the milling media. Third, wet milling improves efficiency. The liquid medium enhances powder flow and fracture, resulting in a more uniform particle distribution and more consistent mixing.

Other additives like wax, or polyethylene glycol (PEG), or synthetic rubber are used as an organic binder to provide temporary bonding between powder particles during the later pressing process.

Step 2: Drying & Granulation

After wet milling, the slurry must first go through drying, screening, and granulation to become a free-flowing powder with uniform bulk density. Only in this form can the material be fed smoothly into automatic presses for producing carbide blanks.

In most cases, this step is completed by a spray tower. A spray tower is a large, enclosed system designed to convert liquid slurry into fine, spherical granules within a very short time. During operation, the slurry is atomized into tiny droplets and introduced into a stream of hot air. The moisture evaporates almost instantly, leaving behind dry granules with controlled particle size and good flowability.

Step 3: Pressing & Compaction

Once the granulated powder is ready, the next step is pressing. This process forms the powder into a solid shape, known as a green compact, which will later be sintered into carbide blanks.

For large-scale production, automatic presses are the most common equipment. These machines apply uniaxial or biaxial pressure through rigid dies, making them suitable for simple geometries such as squares, discs, or rectangular bars. Automatic pressing offers high efficiency and good consistency, which is why it is widely used for standard tungsten carbide blanks.

For more complex shapes, larger sizes, or applications requiring extremely uniform density, isostatic pressing is preferred. In cold isostatic pressing, the powder is filled into a flexible mold, usually a rubber sleeve, and placed inside a high-pressure chamber. Pressure is transmitted through a liquid medium, such as oil or water, acting equally in all directions. This method produces green compacts with very uniform density, making it a common choice for high-end cemented carbide blanks.

Green compacts are strong enough for handling but still very fragile. At this stage, only simple pre-machining operations, such as surface grinding, are possible. The strength of the green compact relies on organic binders added during earlier steps.

Step 4: Sintering

Sintering is the most critical step where carbide blanks gain their final mechanical properties. During this stage, a series of complex physical and chemical changes take place.

The process starts with dewaxing. The green compacts are slowly heated to a relatively low temperature, typically between 300°C and 600°C, under a protective atmosphere. This step removes the organic binder (wax, PEG, or rubber) completely and safely.

After debinding, the blanks enter vacuum sintering, which is the most common and core process in carbide manufacturing. Sintering is carried out at high temperatures, usually above 1300°C to 1500°C, in a vacuum sintering furnace. At this temperature, the binder (Co or Ni) melts and bonds carbide particles together, allowing the material to reach near-theoretical density with very low porosity.

To further eliminate residual micropores, some manufacturers apply low-pressure or overpressure sintering. In the final stage of vacuum sintering, an inert gas such as argon is introduced under controlled pressure. This additional pressure helps close remaining pores and improves internal density.

For applications requiring the highest reliability, hot isostatic pressing (HIP) is used. HIP can be performed as a separate post-sintering process or integrated into the sintering cycle using a sinter HIP furnace. During HIP sintering, high-temperature and isotropic gas pressure are applied simultaneously. This process can completely eliminate internal porosity and significantly improve toughness, transverse rupture strength, and long-term reliability. For cutting tools, dies, and mining-grade tungsten carbide blanks, HIP is often considered a standard requirement rather than an option.

Step 5: Further Processing (Optional)

After sintering, carbide blanks can be delivered in different conditions depending on the customer's requirements. In general, there are two common states.

The first option is the sintered carbide blanks. The surface usually shows slight sintering gloss or a thin decarburized layer, and the dimensions are intentionally left with machining allowance. This state is suitable for most applications, as customers typically perform their own finishing operations based on specific design needs.

For customers with higher precision requirements, carbide blank suppliers may offer rough-machined blanks. In this case, additional processes such as centerless grinding, surface grinding, or double-end face grinding are applied. These operations remove the surface layer formed during sintering and allow tighter control of dimensions and geometric tolerances. However, even after rough machining, the product is still considered a blank rather than a finished part.

Step 6: Quality Inspection

Before being sold as carbide blanks , all products must pass a complete quality inspection process, including density, hardness (HRA), transverse rupture strength (TRS), and metallographic examination (porosity level, WC grain size, and cobalt distribution). Qualified tungsten carbide blanks should show uniform microstructure with controlled grain growth and minimal porosity.

A professional carbide blanks manufacturer should be able to provide inspection reports for each batch, including metallographic photos and mechanical property data. This level of transparency is an important indicator when buyers evaluate different carbide blanks suppliers and compare their quality capabilities.

Conclusion

The manufacturing of carbide blanks is a complex and highly specialized process. It requires much more than basic manufacturing capability. Technical know-how, practical experience, and dedicated equipment all play critical roles. When sourcing materials from global carbide blanks suppliers , a clear understanding of the production process is often the key to making the right decision.