Roads have always been at the heart of human progress. From ancient trade routes to modern highways, they shape how we live, work, and connect. Today, their role goes far beyond transportation: roads drive economic growth, sustain supply chains, aid emergency response, and influence social development.

With such importance, it's natural to wonder: how are roads actually built? What does the road construction process really look like in practice?

(Image Source: Photo by Max on Unsplash.com)

Earlier, I shared an overview of road construction equipment and gave a quick glimpse of the paving workflow. Now, I'll take it a step further and walk you through the key steps of road construction in detail.

Road Construction Steps

In reality, a modern road is the result of a carefully engineered, multi-stage process that balances safety, durability, cost, and environmental factors. Scroll down to explore the road construction steps one by one.

Step 1: Preliminary Planning and Design

Every successful road construction process starts with smart planning. Engineers and planners define the road’s purpose, expected traffic flow, and how it fits into the broader transportation network. This stage also involves surveys, soil testing, and environmental assessments. By identifying potential challenges, such as drainage issues, land acquisition, or safety concerns, early on, teams can save time and money down the line. A solid plan sets the stage for a smooth project.

Step 2: Site Clearing and Demolition

After the plan and design are determined, the first job is to clear up the site, including demolishing old roadways, removing trees and vegetation, or relocating underground utilities. In urban areas, this step also involves rerouting traffic to keep daily life moving. Materials from demolition are either disposed of safely or recycled when possible. Think of this stage as creating a clean canvas before the real construction begins.

Step 3: Earthwork, Grading, and Drainage Preparation

Once the site is clear, heavy machinery levels and shapes the ground. Engineers grade the land to ensure proper slope and drainage, which is critical for ensuring safety, preventing water pooling and future potholes. Soil is compacted layer by layer to build a stable foundation. In mountainous or flood-prone areas, extra measures, like retaining walls or erosion control systems, are added. Without proper grading and drainage, even the best pavement won’t last.

Step 4: Building the Subgrade Layer and the Subbase Layer

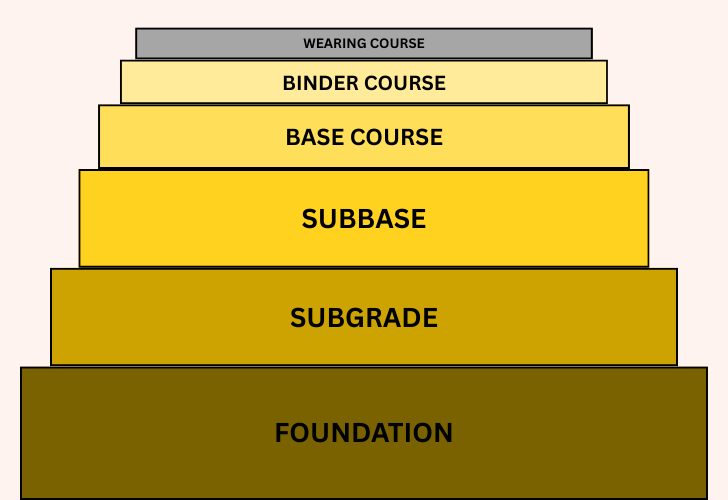

A road is only as strong as the layers beneath the surface, and that starts with the subgrade. In flexible pavements, the subgrade is the deepest part of the foundation. Its upper surface, called the formation, is usually graded with a cross slope to ensure water drains away from the pavement, keeping the foundation stable. Since the subgrade is mostly compacted natural soil, engineers must carefully assess its strength and condition.

Directly above the subgrade lies the subbase. The subbase layer is not always required for walkways, but for any road that needs to handle vehicles, it is absolutely essential. The subbase can be made with either unbound granular materials or cement-bound mixtures. Unbound options typically include crushed stone, slag, recycled concrete, or slate. Cement-bound materials, on the other hand, come in several types, such as CBM 1 (soil cement), CBM 2, etc. The thickness of the subbase layer varies depending on the type of pavement and expected load. For garden paths, it typically ranges from 75 to 100 mm; for driveways and public footpaths, 100 to 150 mm is common; heavily used roads require 150 to 225 mm, while highways often need even thicker subbase layers to support high traffic volumes. This layer is compacted to a precise density. Any weak spots are repaired immediately, because a poor subbase is the number one reason roads fail early.

Step 5: Building the Base Layer (Base Course)

The base layer, or base course, sits just below the asphalt surfacing, beneath the wearing course and, in some designs, beneath a binder course. Depending on the road’s construction, it may rest directly on the subbase or, in lighter-duty pavements, directly on the subgrade. Every vehicle passing over the road generates stresses in the surface layers, and it is the base course that distributes these stresses evenly down to the foundation. By doing so, it prevents excessive rutting, deformation, or cracking, helping the pavement perform reliably over its intended 15–20 year service life. A typical base course is 100 to 300 mm thick, although the exact depth depends on the strength of the layers beneath. It is usually made from high-quality aggregates, including:

- Unbound aggregate, such as crushed stone, is carefully compacted to at least 95% density to form a stable foundation.

- Bitumen-bound aggregate, which improves cohesion and durability.

- Cement-bound aggregate, sometimes used for extra strength, though it carries a risk of cracking and requires ongoing maintenance.

Stabilization technology, such as geogrid reinforcement, is employed in modern road construction. This method can greatly extend the pavement’s lifespan without increasing thickness.

Step 6: Laying the Binder Course

Now comes the layer between the base layer and the surface course (wearing course), the binder course. This layer is made from coarser and larger aggregates mixed with stone particles. Its common thickness ranges from 50 to 100mm, thicker than the wearing course. The binder course provides structural strength and distributes the traffic load from the wearing course into the base course.

Step 7: Applying the Surface Layer (Wearing Course) and Finishing Touches

The surface layer, often called the wearing course, is the very top of a pavement, the part we actually see, drive, and walk on every day. Its purpose goes far beyond appearance: this layer provides a smooth, durable, and skid-resistant surface that ensures safe and comfortable travel.

- In flexible pavements, the wearing course is typically made of asphalt concrete, a mix of construction aggregate bound together with bitumen. This combination not only delivers the necessary strength to resist rutting and abrasion from traffic but also forms a waterproof shield, preventing rainwater from seeping into and weakening the lower pavement layers.

- In rigid pavements, by contrast, the surface is a slab of Portland cement concrete, designed to withstand heavy loads over long periods.

Construction of the surface layer requires precision. After paving, heavy rollers compact the asphalt or concrete to remove air pockets and achieve a uniform, weatherproof finish. Only once this layer is in place do contractors add the finishing touches, such as road markings, signage, and safety barriers, transforming the site from a construction zone into a functioning roadway.

Step 8: Quality Control, Transitions, and Final Inspection

The last stage is all about making sure the road is safe and built to last. Engineers test density, smoothness, and drainage, often using strict tolerance limits (for example, checking undulations with a straight edge). Transitions to existing roads, driveways, or parking lots are carefully graded so vehicles don’t hit bumps or dips. Once all standards are met, structural, safety, and environmental, the road is officially handed over for public use.

*All of the above images are not intended for commercial use.